| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

2024年6月25日火曜日

Dirk EhntsさんによるXでのポスト Desan

2024年6月24日月曜日

weber2024

https://www.blogger.com/blog/post/edit/4746200653128420172/145563134824431749

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Towards a Post-neoliberal Stabilization Paradigm: Revisiting International Buffer Stocks in an Age of Overlapping Emergencies Based on the Case of FoodIsabella M. Weber* Merle Schulken Abstract The neoliberal stabilization paradigm of interest rate hikes and austerity left economies around the world unprepared for the shocks to essentials experienced in the overlapping emergencies of war, conflict, climate change, and pandemic. This presents a window of opportunity for a paradigm shift. Neoliberalism became hegemonic through stabilization policy. Post-neoliberalism will require an alternative stabilization paradigm. In this paper we revisit the classic reasoning for buffer stocks by Keynes, Kaldor, Graham, and others as a starting point for this paradigmatic shift. At the core of the neoliberal stabilization paradigm are the assumptions that competitive markets are efficient and that relative price changes ought to be separated from macro-outcomes. In contrast, buffer stock reasoning starts from the inherent instability and inefficiency of commodity markets. Price volatility in essential commodities can lead to sellers’ inflation because of the interaction with administered prices in the industrial sector and can hamper growth and development prospects. We illustrate that the buffer stock reasoning can help understand the 2020-2023 world food price crisis and propose a multi-layered buffer stock system for food staples as a steppingstone in a gradualist transition to post-neoliberalism and a tool for a green transformation of agriculture. Keywords: Inflation, post-neoliberalism, food, stabilization policy, climate change, development Acknowledgements: We are grateful for funding of this research by the Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung, TMG Think Tank for Sustainability, and Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung. We are indebted to our interview partners who have kindly shared their insights with us in long and detailed conversations. We would like to thank Cornel Ban, Lena Bassermann, Alexandros Kentikelenis, Lena Luig, Gregor Semieniuk, Quinn Slobodian, Jan Urhahn, and the participants of a workshop on post-neoliberal global governance of the History and Political Economy Project for helpful comments on an earlier version of this paper. Introduction The world has entered an age of overlapping emergencies. Climate change is a reality in the here and now. Extreme weather events are occurring with greater frequency and intensity and are more likely to affect multiple world regions at once (Kornhuber et al., 2023). This has potentially far-reaching

consequences for economic activity, for example reducing agricultural yields and disrupting transportation and energy systems (Markolf et al., 2019; Mehrabi, 2020). At the same time, the geopolitical order is becoming increasingly unstable. In 2023 the Global Peace Index deteriorated for the 9th consecutive year (Institute for Economics & Peace, 2023). In this global constellation supply shocks become frequent. The experience since the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrates that if shocks hit systemically important sectors like energy, food, transportation, or housing they can trigger sellers’ inflation (Weber et al., 2022; Weber and Wasner, 2023). Price and profit spikes in upstream sectors like commodities, energy, and shipping are cost shocks to downstream firms. These cost shocks coordinate price hikes as firms seek to protect their profit margins. It is this pricing behavior of sellers’ that translates local shocks into a generalized inflation that is for the larger part accounted for by profits. For now, the neoliberal policy of interest rate hikes has been the predominant if not exclusive policy response to inflation. But even believers of the neoliberal stabilization paradigm will have to eventually concede that frequent shocks to systemically important sectors cannot be addressed with a proverbial “cold turkey” every time. In fact, rich countries have already complemented the neoliberal playbook with fiscal expansion (US) and various forms of energy price controls (Europe) (Dao et al., 2023). For the worlds’ poorest countries rate hikes are devastating and they lack the fiscal and policy space for such complementary measures. Neoliberalism became hegemonic first as a new stabilization regime. Post-neoliberalism will require an alternative approach to stabilization. We argue that in an age of overlapping emergencies such a new paradigm requires a refocusing on stabilization policies for essential sectors that have the potential to unleash systemic instabilities when hit by shocks. We revisit the classic case for public buffer stock systems of Keynes (1938, 1971c [1926], 1971b [1923], 1971a [1930], 1974 [1942]), Kaldor (Hart et al., 1980 [1963]; Kaldor 1934, 1976, 1980b [1962], 1980a [1952], 1987), Graham (1937, 1944) and others. The buffer stock question in their analysis is not just a tool but provides an alternative theoretical perspective. The classic case holds that commodity markets are inherently unstable and hence inefficient even when perfectly competitive. They see public storage to dampen price and quantity fluctuations at the sectoral level as key to global macro stabilization. We show that at the critical 1970s juncture such buffer stocks were part of the New International Economic Order

(NIEO) agenda and presented a real alternative to the neoliberal road but were ultimately questioned by neoclassical welfare analysis and crushed by the Federal Reserve’s sharp interest rate hike in 1979 (the so-called “Volcker Shock”), and the market fundamentalist liberalization and privatization conditionalities of the Washington Consensus. We argue that the neoliberal policy paradigm centered on free prices left people and economies unprepared for the mega shocks of overlapping emergencies in recent years, while benefitting gigantic corporations. To illustrate this point, we present the case of food. Using the reasoning of the classic case for buffer stocks and drawing on 25 interviews with businesses and unions in the food sector, agricultural policy experts, food bank representatives, and academic food system experts from Global South and Global North countries, we argue that food price spikes are inefficient and lead to devastating humanitarian and macroeconomic outcomes. We present a case for a multi-layered and internationally coordinated public buffer stock system for food staples as a first important step towards a post-neoliberal stabilization paradigm. The Classic Case for Global Buffer Stocks: Sectoral Stabilization for Growth and Development The economic case for buffer stocks has its origins in Chinese statecraft with the ancient so-called ever normal granary. The basic operating principle of such a public stockholding facility was for the state to participate in the market in order to stabilize the price of grain. The public granaries were meant to buy in times of good harvests when prices are low and re-sell on the open market when grain supplies decline with the seasons and prices increase or to address poor harvests and disasters that trigger price spikes (Weber, 2021b, 2021a). The ever normal granary became a model for buffer stocks envisioned as part of the stabilization policy toolbox when modern macroeconomics emerged in the interwar period (Fantacci, 2012; Woods, 2022). Roosevelt’s New Deal administration implemented what was called an American ever normal granary (Bodde, 1946).1 In a rare agreement, both Keynes and Hayek endorsed aspects of a plan for a global buffer stocks system laid out by Benjamin Graham that was envisioned as a cornerstone of the postwar global governance system

(Graham, 1944; Hayek, 1948; Keynes, 1974 [1942]).2 Although ultimately not implemented under the Bretton Woods system, proposals for global buffer stocks remained an important pillar of macroeconomic stabilization in the work of leading economists of the postwar era like Nicholas Kaldor and Jan Tinbergen (Hart et al., 1980 [1963]; Kaldor, 1976). In this section we introduce three key elements of the case for global buffer stocks drawing on classic contributions. 1. Threat of shortages of essentials The classic case for buffer stocks starts from the recognition that some goods are more essential than others for human livelihoods or for the production system taken as a whole (FAO, 1946; Graham, 1937; Woods, 2022). The concept of essential is akin to Sraffa’s basic commodity or the more recent discussions around critical inputs and systemic importance (Weber et al., 2022). The idea is that there are things that people or producers cannot do without. The threat of a shortage or the lack of access to these goods has systemic implications.3 For example, as the recent energy crisis has illustrated for the German economy, oil, gas, and coke products make up one group of commodity inputs that are essential for price stability and export competitiveness until renewable energies are sufficiently built out and thus affect the production system as a whole (Krebs and Weber, 2024; Weber, et al., 2024). Providing adequate access to energy at the level of the individual is also essential for securing human livelihoods. Food commodities represent another group of commodities that are essential both for price stability and for human livelihoods (ibid.; Weber et al., 2022). Goods can also be rendered essential if a country’s economy depends on its export revenues to ensure the livelihoods of its citizens, as is the case for commodity export dependent Global South countries (Kaldor, 1980b [1962]). Out of 134 low- and middle-income countries, 97 are net food importers, out of which 60 are highly commodity export dependent (FAO et al., 2019, p. 64). Movements in commodity prices affect the relative prices of these countries’ exports and imports, potentially draining foreign exchange reserves, causing a devaluation of the currency, or resulting in

2 See Telles (2023) for a review of the debate between Keynes and Hayek on plans for a world commodity reserve currency. 3 See Weber et al. (2022) for a formal analysis of pathways to systemic significance using input-output modeling.

1 The New Deal Ever Normal Granary did not primarily rely on public storage but provided loans to farmers for storage unlike its Chinese antecessor that combined participation in the grain market through public granaries with loan policies. The US government still controlled the amount of product in storage by setting the terms of these loans, incentivizing stockholding, and limiting lands for agricultural cultivation, but the products were for the most part stored by private market participants.

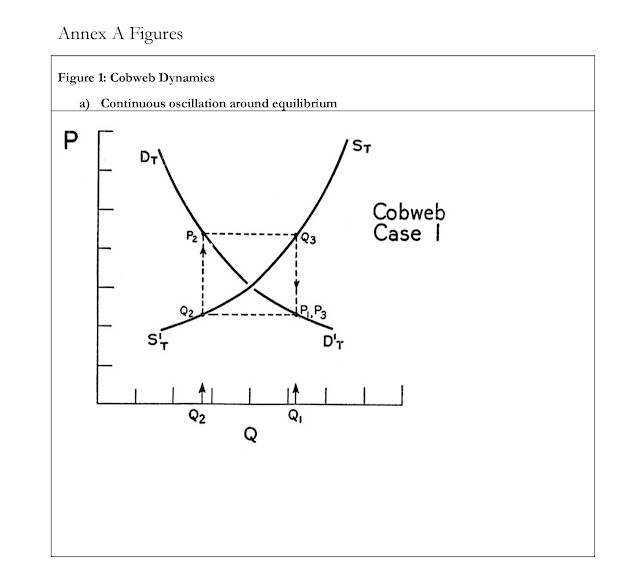

economic disruptions that affect people’s incomes (ibid.). A fall in export commodity prices can thus reduce these countries’ ability to purchase essential commodities like staple foods on international markets and disrupt their domestic economies making it harder for vulnerable groups to access essentials. Buffer stocks can help ameliorate the threat of a shortage of durable essentials by ensuring the availability of physical supplies across time and space. They also aim to ensure accessibility of essentials by preventing prices from spiking up too high or a collapse of incomes from prices dropping too low. By contrast, emergency reserves for example of food or medical supplies only aim to prevent physical shortages. As Amartya Sen (1982) reminds us in his canonical work on famine prevention, deprivation can be caused not only by physical shortages but also by a lack of economic access to essentials by groups that see a collapse or lack of income or are priced out. Buffer stocks address the price part of this problem for all consumers and the income part for agricultural producers. They are a complementary tool to measures that ensure sufficient incomes for all groups. Buffer stocks are also not suited for all essentials but can be used for sufficiently homogenous, storable commodities that allow for countercyclical purchase and sale on the part of a stockholding system. 2. Inherent instability of commodity markets The classic microeconomic case for buffer stocks rests on the observation of an inherent instability in commodity markets. As Kaldor reminds us, the “economic function of a rise in price is to encourage producers and to discourage consumers; that of a fall in price is the opposite.” (Kaldor, 1980a [1952], p. 65). This is what should lead to equilibrium in standard theory. But if the supply adjustments to the price signal are slow, there may never be an equilibrium. Reasons for slow supply adjustments include high capital intensity of production and a time lag between production decisions and sale (Keynes, 1971c [1926]). The result can be an over- and undershooting of prices and quantities in a cobweb dynamic (Kaldor, 1934; Tinbergen as in Ezekiel, 1938). Depending on the elasticities of supply and demand, this dynamic can result in a continuous oscillation around an equilibrium; an explosive spiraling out of equilibrium; or a convergence to equilibrium (Figure 1a-d; Ezekiel, 1938; Tinbergen, 1930). As Ezekiel points out, the cobweb theory implies a crucial departure from standard neoclassical theory which “rests upon the assumption that price and production, if disturbed from their

equilibrium, tend to gravitate back toward that normal” (1938, pp. 278-279). In contrast, “the cobweb theory demonstrates that, even under static conditions, this result will not necessarily follow” (ibid., p. 279). Even in commodities that follow the convergent dynamic (Figure 1c), if for example due to weather shocks, “abnormally large or small crops… cause a marked departure from normal” and start again and again “a series of convergent cycles”, stability might never be reached (ibid., p. 273). Simply put, the invisible hand can fail to bring about efficient resource allocation. This is not the result of market imperfections but is the likely outcome under perfect competition if there is a time lag (ibid., p. 280). Storage can in principle overcome the slowness of adjustment. But as Keynes argues: “It is an outstanding fault of the competitive system that there is no sufficient incentive to the individual enterprise to store surplus stocks of materials, so as to maintain continuity of output and to average…periods of high and of low demand” (Keynes, 1938, p. 449). The reasons for a socially suboptimal level of private storage are (Keynes, 1938): First, the cost of holding stocks. Second, a lack of incentive for firms that use the commodity as an input to hold large stocks in excess of current production needs since their output prices tend to move with their key (commodity) input prices on their way up. Third, the co-movement between macroeconomic fluctuations and commodity prices amplify the risk of holding large inventories. Private speculators can increase storage, but they do not fix the problem of endogenous instability in Keynes’ view. The speculators’ liquidity fluctuates with the macroeconomy and they tend to be reluctant to buy stocks in a downturn (Keynes, 1938, 1971b [1923]). Speculation can hence exacerbate fluctuations due to procyclical expectations and herd behavior (Keynes, 1938, 1971c [1926]). Keynes held that the trading of commodity futures can help stabilize the prices that producers receive but does not stabilize fluctuations in spot prices as it does not resolve the time-lag and elasticity issues that make commodity markets inherently unstable (Keynes, 1971a [1930]). Hence, public stockholding is necessary to overcome the slowness of supply and demand adjustments and stabilize commodity markets.

3. Macroeconomic instabilities from microeconomic fluctuations

The possibility of cobweb dynamics in commodity markets implies at the level of the economy as a whole that there is “no ‘automatic self-regulating mechanism’ which can provide full utilization of resources” and “unemployment, excess capacity, and the wasteful use of resources may occur even

when all the competitive assumptions are fulfilled” (Ezekiel, 1938, pp. 279-80). In addition to inefficient use of resources, the classic macroeconomic case for buffer stocks rests on the observation that large price swings in essential commodities can destabilize the whole economy while depressing the terms of trade of commodity exporting countries and introducing a long-term trend toward global economic stagnation (Graham, 1937, 1944; Hart et al., 1980 [1963]; Kaldor, 1976, 1980b [1962]). This argument is derived from a two-sector model. The two sectors may refer to the urban-industrial and the agricultural-rural sectors within one country or to commodity exporting countries and industrialized countries. The dynamic between the two sectors hinges on their different pricing regimes (Kaldor, 1976).4 In the primary sector, sellers are price takers. In contrast, sellers of industrial products are price makers with administered prices, i.e. cost plus mark-up pricing when costs move up and holding the line pricing when costs fall. In the primary sector, shifts in demand or supply result in price fluctuations. In the industrial sector, shifts in demand or supply are met with quantity rather than price adjustments – either by accumulating/depleting inventories or by hiring/laying off additional workers. The implication of the difference in the price mechanisms is that “any large change in commodity prices – irrespective of whether it is in favor or against the primary producers – tends to have a dampening effect on industrial activity” (Kaldor, 1976, p. 706). A fall in commodity prices does not lead to a fall in industrial prices as firms resist lowering prices and workers resist falling real wages. The resulting decline in the purchasing power of the primary sector and the lower rate of investment in that sector reduces the demand for the industrial sector which slows down growth pushing commodity prices down further (Hart et al., 1980 [1963]). Instead of stimulating demand, a collapse of commodity prices caused by a recession in the industrial sector may induce a depression and deflation, as in the case of the Great Depression in the United States (Kaldor, 1976). An increase in the prices of primary goods does not benefit the primary sector or global growth in a sustained way either as the example of the commodity price boom and ensuing stagflation of the 1970s illustrates (Kaldor, 1976). Due to the price-setting power of industrial firms, a primary sector cost shock unleashes in industrial countries a process recently reintroduced as “sellers’ inflation” (Weber and Wasner, 2023): the cost increase is “passed through the various stages of production

4 For a more formal treatment of Kaldor’s model, see Kanbur and Vines (1986) and Spraos (1989).

into the final price with an exaggerated effect – it gets ‘blown up’ on the way by a succession of percentage additions to prime costs which mean, in effect, an increase in cash margins at each stage.” (Kaldor, 1976, p. 706). Higher industrial goods prices diminish the improvement in the terms of trade that the primary sector experienced as the prices for its goods went up. If governments in industrialized countries respond to sellers’ inflation with macroeconomic tightening aimed at dampening demand, this slows growth in industry and thus brings down commodity prices again (Kaldor, 1976). The income from high commodity prices on the part of primary producers could in principle offset some of the decline in demand from industrial countries’ austerity. But commodity incomes often take the form of profits that do not necessarily flow into domestic consumption or investment (ibid.). With unpredictable commodity prices, producers are less able to make long-term investments (Kaldor, 1987 [1983], p. 554). Similarly, fluctuating export revenues inhibit long-term economic policy-making in exporting countries, stifling investment (Kanbur, 1984, p. 351) This can be detrimental for long-run prosperity (ibid.). Stabilizing commodity prices thus creates a win-win for industrial and commodity-dependent countries by improving global macroeconomic stability and growth. The primary sector receives more predictable revenue streams and better terms of trade vis a vis the industrial sector. And the industrial sector gains a source of counter-cyclical demand from the primary sector and avoids taking costly measures against cost-push inflation. From this macroeconomic perspective buffer stocks are a key ingredient for “the harmonious development of the world economy” (Kaldor, 1976, p. 707). Since commodity markets are global, the preferred level of operation of buffer stock proponents has tended to be international. The accumulation of stocks should start off when the relevant commodities are in excess supply and was meant to be financed by issuing an international currency against these stocks (Graham, 1944; Hart et al., 1980 [1963] pp. 146-151; Hayek, 1948 [1943]; Keynes, 1974 [1942], p. 304). In some proposals a buffer stock agency would issue an international currency to purchase commodities and “destroy” the currency as it sold commodities back into the market (e.g. in Graham, 1944; Hart et al,. 1980; Hayek, 1948). In other proposals money creation was left to a

separate international institution or to national governments and central banks (Keynes, 1974 [1942]). Independent of the institutional arrangement liquidity on international markets would increase countercyclically providing an automatic macroeconomic stabilizer: when commodity prices fall during a global downturn the agency buys commodities to prop up prices and this requires the issuing of currency, and during a commodity boom in the economic upswing it sells which absorbs liquidity. Such an international commodity reserve currency has also been seen as a potential solution to global monetary management (Ussher, 2009). Financing for the buffer stock authority was extended through an overdraft facility or by governments or central banks cooperating in holding shares in the buffer stock as reserves. Opinions diverged on whether a global buffer stock system would need to be holistic from the start stabilizing an index of commodity prices as Graham, Hayek, and originally Hart, Kaldor and Tinbergen proposed, or whether a more gradualist approach could be pursued in the building up of such a system where an international agency would stabilize individual commodity prices – which is what Keynes and later also Kaldor tended towards. Another dividing line among buffer stock proponents has been the question of rules versus discretion akin to the old debate around central banks’ monetary policy. Hayek (1948 [1943]), for example, as is characteristic for the neoliberal policy nihilism advocated for a rule that would mimic the gold standard. Keynes (1974 [1942]) leaned towards policy activism and discretion not only in monetary policy but also in the management of buffer stocks.

The New International Economic Order and the Rise of the Neoliberal stabilization paradigm

Global buffer stocks as a path-not-taken in the 1970s

The question of the management of essential commodities returned to the international agenda in the wake of the collapse of the Bretton Woods system and the commodity price shocks (Gilman, 2015; Toye, 2014, pp. 44-47). A mix of declining agricultural productivity growth and droughts had drawn down the surplus stocks of food commodities in the United States and the European Economic Community (Shaw, 2007, pp. 115-121). When crops failed in multiple parts of the world at once in 1972, grain prices shot up, coinciding with a rise in oil prices due to OPEC’s pricing decision and a more general price increase for commodities (Cooper et al., 1975; Garavini, 2019). The price shocks set off a cost-push inflation in the Global North and contributed to famine and

balance of payment problems in many Global South countries while creating large revenue streams to oil exporters (Labys and Maizels, 1993; World Bank, 1982). In this context, the macroeconomic case for buffer stocks gained new relevance. In terms of politics, newly independent Global South countries gained the majority of votes in UN institutions. Encouraged by OPEC’s success in unilaterally instituting higher oil prices, Global South countries organized through the Group of 77 started to coordinate more forcefully on economic issues (Corea, 1992, 27; Toye, 2014, pp. 43-56). Faced with domestic inflation and the threat of commodity cartels, rich country governments opened up to negotiations (Cline, 1979). Global South countries struck a first victory with the adoption of the declaration on the establishment of a New International Economic Order (NIEO) by the UN General Assembly in 1974. An International Program for Commodities (IPC) introduced by UNCTAD and to be financed through the creation of a Common Fund (Cline, 1979; UNCTAD, 1977) became a cornerstone of the NIEO agenda. Buffer stocks for two groups of essentials were envisioned: commodities in which Global South countries were import-dependent, importantly grain, or export-dependent, for example cocoa, coffee, jute, sugar, and minerals (UNCTAD, 1977). At the World Food Conference in Rome in 1974, countries agreed on the International Undertaking on World Food Security. This resolution declared intentions to negotiate a reserve system of nationally held but internationally coordinated stocks of staple foods (UN World Food Conference, 1974). A United States proposal for an international grain reserve system covering wheat and rice was negotiated throughout the 1970s (Cline, 1979; Gulick, 1975; Sarris et al., 1979). In the end, the initiatives of the NIEO were short-lived and discussions about commodity price stabilization were no exception. The negotiations about the grain reserve showed promise of being concluded towards the end of the 1970s but ultimately failed to identify a target price for stabilization that was acceptable to all parties (Cline, 1979; Friedmann, 1993). Negotiations on the Common Fund of the IPC dragged on far longer than expected (the Fund was not fully ratified until 1988) and in absence of this financing vehicle only few International Commodity Agreements were concluded, none of which featured price stabilization (Corea, 1992, pp. 140-145). Had the political and structural conditions that catalyzed the creation of the NIEO lasted another decade, perhaps agreements could have been reached (Corea, 1992, pp. 153-162).

The plans for commodity price stabilization had been careful to highlight the win-win case for importers and exporters, Global North and Global South countries alike. The classic case for buffer stocks with its focus on the inherent instability of commodity markets and global macroeconomic benefits from stabilization dominated the policy imaginary and measures for price stabilization were understood to operate within a broader policy framework of North-South cooperation and growth. But negotiations about who should contribute to financing stocks, within which bands prices should be stabilized, the size of the required stocks and hence the cost led to a paradigmatic shift from the classic framework to neoclassical welfare analysis (Brown, 1980, pp. 100-137; Cline, 1979; Corea, 1992, pp. 136-163), which ultimately paved the way for neoliberalism. Neoclassical welfare analysis as a slippery slope towards neoliberalism The application of neoclassical welfare analysis to assess commodity price stabilization schemes was nothing new in the 1970s (Kaldor, 1980a [1952]; Massell, 1969; Oi, 1961; Waugh, 1944), but in the 1970s welfare analysis became a crucial political battleground in the negotiations over the IPC and Common Fund. Where the classic case for buffer stocks stressed that the behavior of rational agents in competitive markets can lead to socially sub-optimal dynamics at the macroeconomic level, the neoclassical analysis represented the aggregate through a representative agent (Turnovsky, 1978). This eliminated the socially suboptimal outcomes of commodity price volatility of the classic case by assumption. Cobweb dynamics were replaced altogether by returning to standard theory assuming instantaneous adjustments to equilibrium (e.g. Brook and Grilli, 1977). Oscillation and divergence dynamics, i.e. the movement of market prices around an equilibrium price or away from an equilibrium price as explained in section 2 (see Figures 1a, b), were ruled out with assumptions about rational expectations paving the way for the efficient market hypothesis (Muth, 1961; Smith, 1978). On the back of the neoclassical assumption that markets converge to equilibrium, the problem of insufficient storage and price volatilities was reframed as one of market imperfections. Incomplete futures and insurance markets, price rigidities, asymmetric information, trade restrictions, excessive speculation, or the threat of government intervention were seen as the causes why commodity markets did not settle in equilibrium (Labys, 1978; Newbery and Stiglitz, 1981; Sarris and Taylor, 1978; Wright and Williams, 1982; Smith, 1978). The focus in the assessments of the size of buffer stocks was now on crowding out private storage as rational market participants would account for the public stockholding which implied that buffer stocks would need to be prohibitively large to

effectively operate (Hallwood, 1977; Helmberger and Weaver, 1977; Miranda and Helmberger, 1988; Newbery and Stiglitz, 1981, pp. 37-38). The Kaldorian two sector model of the world where commodity price shocks could translate into cost-push inflation along the supply chain was replaced with a general equilibrium model where the incidence of price instability in one goods market is (partly) offset by shifts in other markets (Kanbur 1984, p. 347; Newbery & Stiglitz, 1981, p. 19; Smith, 1978). This largely insulated the macro-outcome of a change in the general price level from volatilities in relative prices and inflation became a matter of macro policy alone (Weber et al., 2024). The abandonment of assumptions about different sectoral pricing regimes also eliminated the theoretical possibility of systematically depressed terms of trade for commodity exporters. Overall, the lack of a dynamic analysis of development over time in the static world of the microeconomic models meant that global win-win dynamics became inconceivable. The early cost-benefit analyses still found that when consumers and producers are considered together, more stable prices are always welfare enhancing (Massell, 1969; Turnovsky, 1978). However, the gains from stabilization are distributed unequally in neoclassical welfare analysis with either consumers or producers losing income to the other group in the long run. Unless one group compensates the other, price stabilization thus turns into a tale of winners and losers. Empirical studies soon suggested that, contrary to policymakers’ expectations, for many of the commodities suggested for UNCTAD’s IPC, Global South countries stood to lose in the long run while Global North countries were the net winners of stabilization (Brook and Grilli, 1977; Labys 1978; Newbery and Stiglitz, 1981, pp. 43-47). However, results were extremely sensitive to model specifications, which implied that the findings of different studies were inconclusive (Behrman, 1979; Sarris et al., 1979). Despite this conceptual shift that proved consequential in the long run, the assessment of economists at the time was by no means an outright dismissal of the IPC. Even the ordoliberal Donges (1977), for example, identified by Cline (1979, p. 5) as one of the most hostile voices on the NIEO saw some benefits in commodity price stabilization. Many authors of microeconomic studies at the time were transparent about the limitations of their approach and thus refrained from making definitive statements about the desirability of buffer stock schemes (Brown, 1980; Newbery and

Stiglitz, 1981; Brook and Grilli, 1977). It is only under neoliberalism that the dismissal of buffer stocks became a default position. But neoclassical welfare analysis came to pave the way for the neoliberal dictum of the primacy of free prices plus cash compensation (Jäger and Zamora Vargas, 2023; Krebs and Weber, 2024; Weber, 2018) by overruling the classic perspective of inefficient price fluctuations. Instead of seeing price stabilization as a goal due to its benefits for growth and development, welfare analysis shifted the focus to alternative policies meant to address negative consequences of commodity price instability while preserving the full fluctuation of market prices that were now seen as efficient signals as long as imperfections were removed (Brook and Grilli, 1977; Newbery and Stiglitz, 1981, pp. 12-16). From this neoclassical stance, recommended policies at the domestic level included removing market imperfections with better and more long-term futures markets, improved access to credit markets and crop insurance, while relying on cash transfers to low-income consumers and producers where necessary (Newbery & Stiglitz, 1981, pp. 41-43). At the international level, better information and trade liberalization should improve competition while compensatory financing provides foreign exchange resources to Global South countries when they experience a shortfall of export revenues (ibid. p. 14, pp. 41-43; Brook and Grilli, 1977).5 Goals like improving the ability of producers to plan investments thanks to more stable prices; ameliorating inflationary pressures or contributing to stable aggregate demand were downgraded to positive externalities of a buffer stock scheme to be considered in addition to the main, welfare economics analysis (Smith, 1978; Sarris et al., 1979; Behrman, 1979) – just to be dropped before too long.

:14

ウェーバー2024①

ポスト新自由主義の安定化パラダイムに向けて:食料問題の事例に基づく、重なり合う緊急事態の時代における国際緩衝在庫の再検討Isabella M. Weber* Merle Schulken 要旨 金利引き上げと緊縮財政による新自由主義の安定化パラダイムは、世界中の経済を、戦争、紛争、気候変動、パンデミックという重なり合う緊急事態で経験した生活必需品へのショックに対する備えができていない状態に置いた。これは、パラダイムシフトの好機である。新自由主義は安定化政策を通じて覇権を握った。ポスト新自由主義には、代替の安定化パラダイムが必要となる。本稿では、このパラダイムシフトの出発点として、ケインズ、カルドア、グレアムらによる緩衝在庫に関する古典的な理論を再検討する。新自由主義の安定化パラダイムの中核にあるのは、競争市場は効率的であり、相対的な価格変動はマクロの結果から切り離されるべきであるという仮定である。対照的に、緩衝在庫の論理は、商品市場が本質的に不安定で非効率であるという点から出発する。必需品の価格変動は、工業部門の管理価格との相互作用により売り手のインフレにつながり、成長と発展の見通しを妨げる可能性がある。我々は、緩衝在庫の論理が2020~2023年の世界食糧価格危機の理解に役立つことを示し、ポスト新自由主義への段階的な移行の足がかりとして、また農業のグリーン変革のツールとして、主食用の多層緩衝在庫システムを提案する。キーワード: インフレ、ポスト新自由主義、食糧、安定化政策、気候変動、開発 謝辞: この研究はハインリヒ・ベル財団、TMG 持続可能性シンクタンク、ローザ・ルクセンブルク財団から資金提供を受けた。長時間にわたる詳細な対話で洞察を共有してくれたインタビューパートナーにも感謝する。本論文の初期バージョンに対して有益なコメントをくれた、Cornel Ban、Lena Bassermann、Alexandros Kentikelenis、Lena Luig、Gregor Semieniuk、Quinn Slobodian、Jan Urhahn、および歴史と政治経済プロジェクトのポスト新自由主義グローバルガバナンスに関するワークショップの参加者に感謝する。 はじめに 世界は重なり合う緊急事態の時代に突入した。気候変動は今ここにある現実である。異常気象はより頻繁に、より激しく発生しており、一度に世界の複数の地域に影響を及ぼす可能性が高まっています(Kornhuber et al., 2023)。これは潜在的に広範囲に及ぶ影響を及ぼします。

経済活動への影響、例えば農業生産量の減少や輸送・エネルギーシステムの混乱(Markolf et al., 2019; Mehrabi, 2020)。同時に、地政学的秩序はますます不安定になっている。2023年、世界平和度指数は9年連続で悪化した(Institute for Economics & Peace, 2023)。この世界的な状況では、供給ショックが頻繁に発生する。COVID-19パンデミック以降の経験から、エネルギー、食品、輸送、住宅などのシステム上重要なセクターにショックが発生すると、売り手インフレが引き起こされる可能性があることが明らかになっている(Weber et al., 2022; Weber and Wasner, 2023)。商品、エネルギー、海運などの上流セクターでの価格と利益の急上昇は、下流企業へのコストショックである。これらのコストショックは、企業が利益率を守ろうとする際に価格上昇を調整する。売り手のこの価格設定行動こそが、局所的なショックを一般化したインフレへと変換し、その大部分は利益によって説明される。今のところ、金利引き上げの新自由主義政策は、インフレに対する唯一の政策対応ではないにしても、支配的となっている。しかし、新自由主義の安定化パラダイムの信奉者でさえ、システム上重要なセクターへの頻繁なショックを毎回ことわざにある「いきなり断つ」では対処できないことを最終的には認めざるを得なくなるだろう。実際、富裕国はすでに財政拡大(米国)とさまざまな形のエネルギー価格統制(欧州)で新自由主義の戦略を補完している(Dao et al., 2023)。世界の最貧国にとって、金利引き上げは壊滅的であり、そのような補完的な措置を講じる財政的および政策的余地がない。新自由主義は、まず新たな安定化体制として覇権を握った。ポスト新自由主義には、安定化への代替アプローチが必要になるだろう。我々は、緊急事態が重なり合う時代に、このような新しいパラダイムでは、ショックを受けた場合にシステムの不安定性を引き起こす可能性のある重要な部門の安定化政策に再び焦点を当てる必要があると主張する。我々は、ケインズ (1938、1971c [1926]、1971b [1923]、1971a [1930]、1974 [1942])、カルドア (ハート他、1980 [1963]、カルドア 1934、1976、1980b [1962]、1980a [1952]、1987)、グラハム (1937、1944) などの公的バッファーストックシステムの古典的な事例を再検討する。彼らの分析におけるバッファーストックの問題は、単なるツールではなく、代替の理論的視点を提供するものである。典型的なケースでは、商品市場は本質的に不安定であり、完全競争であっても非効率である。彼らは、セクターレベルで価格と数量の変動を抑える公共の備蓄が、世界的マクロ安定化の鍵であると考えている。私たちは、1970年代の重要な転換期に、そのような緩衝在庫が新国際経済秩序の一部であったことを示している。

我々は、自由価格を中心とした新自由主義政策パラダイムによって、近年の重なり合う緊急事態のメガショックに対して人々や経済が備えられず、巨大企業が利益を得たと主張する。この点を説明するために、食料の事例を提示する。緩衝在庫の古典的な事例の論理を用い、食料部門の企業や労働組合、農業政策の専門家、フードバンクの代表者、南半球と北半球の国の食料システムに関する学術的専門家への25回のインタビューを基に、食料価格の高騰は非効率であり、人道的およびマクロ経済的に壊滅的な結果をもたらすと主張する。我々は、ポスト新自由主義の安定化パラダイムに向けた最初の重要なステップとして、主食用の多層的で国際的に調整された公的緩衝在庫システムの事例を提示する。 世界的な緩衝在庫の古典的な事例:成長と発展のための部門別安定化 緩衝在庫の経済的事例は、古代のいわゆる常常穀倉を伴う中国の国政に起源を持つ。 このような公的備蓄施設の基本的な運用原則は、穀物の価格を安定させるために国家が市場に参加することであった。 公的穀倉は、価格が低い豊作の時期に購入し、季節とともに穀物の供給が減少し価格が上昇したときに公開市場で再販するか、価格高騰を引き起こす不作や災害に対処することを目的としていた(Weber、2021b、2021a)。常常の穀倉地帯は、戦間期に近代マクロ経済学が出現したときに安定化政策のツールボックスの一部として想定された緩衝在庫のモデルとなった(Fantacci、2012年、Woods、2022年)。ルーズベルトのニューディール政権は、いわゆるアメリカの常常の穀倉地帯を実施した(Bodde、1946年)。

1 珍しいことに、ケインズとハイエクの両者は、ベンジャミン・グラハムが戦後のグローバルガバナンスシステムの礎として想定したグローバル緩衝在庫システムの計画の側面を支持した。

(Graham、1944年、Hayek、1948年、Keynes、1974年[1942])。2 最終的にはブレトンウッズ体制下では実施されなかったものの、世界的緩衝在庫の提案は、ニコラス・カルドアやヤン・ティンバーゲンなど戦後を代表する経済学者の研究において、マクロ経済安定化の重要な柱であり続けた(Hart et al.、1980年[1963]、Kaldor、1976年)。 このセクションでは、古典的な貢献を参考にして、世界的緩衝在庫のケースの3つの重要な要素を紹介します。 1. 必需品不足の脅威 緩衝在庫の古典的なケースは、一部の商品が人間の生活や生産システム全体にとって他の商品よりも不可欠であるという認識から始まります(FAO、1946年、Graham、1937年、Woods、2022年)。必須の概念は、スラッファの基本商品や、最近の重要な投入物とシステムの重要性に関する議論に似ています (Weber et al., 2022)。人々や生産者にとってなくてはならないものがあるという考え方です。これらの商品の不足や入手不能の脅威は、システムに影響を及ぼします。3 たとえば、最近のエネルギー危機がドイツ経済で示したように、石油、ガス、コークス製品は、再生可能エネルギーが十分に構築され、生産システム全体に影響を及ぼすまで、価格の安定と輸出競争力に不可欠な商品投入の 1 つのグループを構成しています (Krebs and Weber, 2024; Weber, et al., 2024)。個人レベルでエネルギーへの適切なアクセスを提供することは、人間の生計を確保するためにも不可欠です。食料品は、価格の安定と人間の生計の両方に不可欠な商品の別のグループです (ibid.; Weber et al., 2022)。商品の輸出依存度が高い南半球諸国のように、国民の生活を支えるために国の経済が輸出収入に依存している場合、商品は不可欠なものとなる可能性がある(Kaldor, 1980b [1962])。134の低中所得国のうち、97カ国は純食料輸入国であり、そのうち60カ国は商品輸出に大きく依存している(FAO他、2019、p. 64)。商品価格の変動は、これらの国の輸出と輸入の相対価格に影響を及ぼし、外貨準備の枯渇、通貨の切り下げ、または貿易赤字につながる可能性がある。

2 世界商品準備通貨計画に関するケインズとハイエクの論争のレビューについては、Telles (2023) を参照。

3 入出力モデリングを使用したシステム的重要性への道筋の正式な分析については、Weber et al. (2022) を参照。

1 ニューディール・エバー・ノーマル・グラナリーは、主に公共の貯蔵庫に頼らず、貸付政策と公共の穀物倉庫を通じた穀物市場への参加を組み合わせた中国の先駆者とは異なり、農家に貯蔵用の融資を提供した。米国政府は、これらの融資条件を設定し、在庫保有を奨励し、農業耕作地を制限することで、貯蔵されている製品の量を依然として管理していたが、製品の大部分は民間の市場参加者によって保管されていた。

人々の収入に影響を与える経済混乱(同上)。したがって、輸出商品価格の下落は、これらの国々が国際市場で主食などの必需品を購入する能力を低下させ、国内経済を混乱させ、脆弱なグループが必需品にアクセスすることを困難にする可能性がある。バッファーストックは、時間と場所を超えて物理的な供給を確保することにより、耐久必需品の不足の脅威を軽減するのに役立ちます。また、価格が急騰しすぎたり、価格が下がりすぎて収入が崩壊したりしないようにすることで、必需品へのアクセスを確保することも目的としています。対照的に、食料や医療用品などの緊急備蓄は、物理的な不足を防ぐことのみを目的としています。アマルティア・セン(1982)が飢餓予防に関する彼の代表的な著作で思い出させているように、剥奪は物理的な不足だけでなく、崩壊や収入の欠如、または価格が高騰したグループが必需品に経済的にアクセスできないことによっても引き起こされる可能性があります。バッファーストックは、すべての消費者の問題の価格部分と農業生産者の収入部分に対処します。バッファーストックは、すべてのグループに十分な所得を保証する措置を補完するツールです。バッファーストックはすべての必需品に適しているわけではありませんが、在庫システム側で景気循環に逆らった売買を可能にする、十分に均質で貯蔵可能な商品に使用できます。

2. 商品市場の固有の不安定性 バッファーストックの古典的なミクロ経済学的根拠は、商品市場に固有の不安定性を観察することに基づいています。カルドアが指摘するように、「価格の上昇の経済的機能は、生産者を奨励し、消費者を落胆させることです。価格の下落の経済的機能は、その逆です。」(カルドア、1980a [1952]、65 ページ)。これが、標準理論では均衡につながるはずです。しかし、価格シグナルに対する供給調整が遅い場合は、均衡に到達しない可能性があります。供給調整が遅い理由としては、生産の資本集約度が高いこと、生産決定と販売の間にタイムラグがあることなどが挙げられる(ケインズ、1971c [1926])。その結果、価格と数量がクモの巣のような力学で過剰または不足する可能性がある(カルドア、1934年、ティンバーゲン、エゼキエル、1938年と同様)。この力学は、需要と供給の弾力性に応じて、均衡点の周りで継続的に振動したり、均衡点から爆発的にスパイラルアウトしたり、均衡点に収束したりする可能性がある(図1a-d、エゼキエル、1938年、ティンバーゲン、1930年)。

エゼキエルが指摘するように、クモの巣理論は、「価格と生産が、その本来の目的から逸脱すると、価格と生産は、その目的から逸脱すると、価格と生産は、その目的から逸脱すると、価格と生産は、その目的から逸脱すると、価格と生産は、価格と生産が、その目的から逸脱すると、価格と生産が ...

収束的ダイナミクスに従う商品であっても(図 1c)、例えば天候ショックにより「異常に収穫量が多かったり少なかったりして…通常から著しく逸脱し」、何度も「収束サイクル」を開始すれば、安定には至らない可能性がある(同上、273 ページ)。簡単に言えば、「見えざる手」は効率的な資源配分をもたらさない可能性がある。これは市場の不完全性の結果ではなく、時間差がある場合の完全競争下での起こり得る結果である(同上、280 ページ)。貯蔵は原理的には調整の遅さを克服できる。しかしケインズは次のように論じている。「競争システムの顕著な欠点は、生産の継続性を維持し、需要の高低の期間を平均化するために、個々の企業に材料の余剰在庫を保管する十分なインセンティブがないことである」(ケインズ、1938、p. 449)。民間の保管レベルが社会的に最適とは言えない理由(ケインズ、1938年):第1に、在庫を保有するコスト。第2に、商品を投入物として使用する企業には、生産価格が上昇する際に主要な(商品)投入価格と連動する傾向があるため、現在の生産ニーズを超える大量の在庫を保有するインセンティブがない。第3に、マクロ経済変動と商品価格の連動により、大量の在庫を保有するリスクが増大する。民間の投機家は保管を増やすことができるが、ケインズの見解における内生的不安定性の問題を解決しない。投機筋の流動性はマクロ経済とともに変動し、景気後退時には株式の購入に消極的になる傾向がある(ケインズ、1938、1971b [1923])。したがって、投機は景気循環的期待と群集行動による変動を悪化させる可能性がある(ケインズ、1938、1971c [1926])。ケインズは、商品先物取引は生産者が受け取る価格の安定には役立つが、商品市場を本質的に不安定にするタイムラグと弾力性の問題を解決しないため、スポット価格の変動を安定させることはできないと主張した(ケインズ、1971a [1930])。したがって、需給調整の遅さを克服し、商品市場を安定させるには、公的株式保有が必要である。

3. ミクロ経済変動によるマクロ経済の不安定性

商品市場におけるクモの巣ダイナミクスの可能性は、経済全体のレベルでは「資源の完全な利用を可能にする『自動的な自己調整メカニズム』が存在しない」こと、そして「失業、過剰生産能力、資源の無駄遣いが、

バッファーストックの必要性は、「競争の前提がすべて満たされたとき」に初めて証明される(エゼキエル、1938、pp. 279-80)。 バッファーストックを支持する古典的なマクロ経済学的論拠は、資源の非効率的な使用に加えて、必須商品の大幅な価格変動が経済全体を不安定にし、商品輸出国の貿易条件を押し下げ、世界経済の長期停滞傾向をもたらす可能性があるという観察に基づいている(グラハム、1937、1944; ハート他、1980 [1963]; カルドア、1976、1980b [1962])。 この議論は、2 部門モデルに由来する。2 つの部門とは、1 つの国内の都市工業部門と農業農村部門、または商品輸出国と工業国を指す場合がある。 2 つの部門間の力学は、価格設定体制の違いにかかっている (Kaldor, 1976)。4 第一次産業では、売り手は価格受容者である。対照的に、工業製品の売り手は価格決定者であり、管理された価格、すなわち、コストが上昇した場合は原価にマークアップした価格設定を行い、コストが下落した場合はライン価格を維持する。第一次産業では、需要または供給の変化が価格変動をもたらす。工業部門では、需要または供給の変化は、在庫の蓄積/減少、または追加労働者の雇用/解雇のいずれかによる価格調整ではなく数量調整で対処される。価格メカニズムの違いが意味するのは、「商品価格のいかなる大きな変化も、それが第一次生産者に有利か不利かに関係なく、工業活動に抑制効果をもたらす傾向がある」ということである (Kaldor, 1976、p. 706)。商品価格の下落は、企業が価格引き下げに抵抗し、労働者が実質賃金の低下に抵抗するため、工業価格の下落にはつながらない。その結果、第一次産業の購買力が低下し、同産業への投資率も低下するため、工業部門の需要が減少し、成長が鈍化し、商品価格がさらに下落する(Hart et al., 1980 [1963])。工業部門の不況による商品価格の暴落は、需要を刺激するどころか、米国の大恐慌の場合のように、不況やデフレを誘発する可能性がある(Kaldor, 1976)。1970年代の商品価格高騰とそれに続くスタグフレーションの例が示すように、第一次産品の価格上昇は、第一次産業にも世界経済の成長にも持続的な利益をもたらさない(Kaldor, 1976)。工業企業の価格設定力により、一次産業のコストショックは工業国において「売り手のインフレ」として最近再導入されたプロセスを引き起こす(Weber and Wasner, 2023)。コスト増加は「生産のさまざまな段階を経て、

4 カルドアのモデルのより正式な扱いについては、Kanbur and Vines (1986)およびSpraos (1989)を参照してください。

「一次産品価格の上昇は、一次産品価格の上昇に伴って一次産品産業が経験した交易条件の改善を減少させる。先進国の政府が売り手のインフレーションに需要抑制を目的としたマクロ経済引き締めで対応すれば、産業の成長が鈍化し、商品価格が再び下落する(Kaldor, 1976)。一次産品価格の上昇による一次産品生産者の収入は、原理的には先進国の緊縮財政による需要減退の一部を相殺できる。しかし、商品収入は利益の形をとることが多く、必ずしも国内消費や投資に流れ込むとは限らない(同上)。商品価格が予測不可能な場合、生産者は長期投資を行うことが困難になる (Kaldor, 1987 [1983]、p. 554)。同様に、輸出収入が変動すると、輸出国における長期経済政策の策定が妨げられ、投資が抑制される (Kanbur, 1984、p. 351)。これは長期的な繁栄にとって有害となり得る (同上)。したがって、商品価格の安定は、世界的マクロ経済の安定性と成長を改善することにより、工業国と商品依存国にウィンウィンの関係を生み出す。第一次産業は、工業部門と比較して、より予測可能な収入源とより良い貿易条件を得る。また、工業部門は、第一次産業から反循環的な需要源を獲得し、コストプッシュインフレに対するコストのかかる対策を取らなくて済む。このマクロ経済的観点から、緩衝在庫は「世界経済の調和のとれた発展」の重要な要素である(Kaldor、1976、p. 707)。商品市場はグローバルであるため、緩衝在庫の支持者は国際的なレベルでの運用を好んできた。在庫の蓄積は、関連する商品の供給過剰時に開始されるべきであり、これらの在庫に対して国際通貨を発行することで資金調達されることが意図されていた(Graham、1944年、Hart他、1980年[1963年]pp. 146-151、Hayek、1948年[1943]、Keynes、1974年[1942]、p. 304)。いくつかの提案では、緩衝在庫機関が国際通貨を発行して商品を購入し、商品を市場に売り戻す際に通貨を「破壊」する(例えば、Graham, 1944; Hart et al,. 1980; Hayek, 1948)。他の提案では、通貨の創造は、

バッファーストック当局は、独立した国際機関、または各国政府と中央銀行に資金を提供する(ケインズ、1974年[1942年])。制度的取り決めとは関係なく、国際市場の流動性が景気循環に逆らって増加し、自動的なマクロ経済安定化装置として機能する。つまり、世界的不況で商品価格が下落すると、当局は価格を支えるために商品を購入するが、これには通貨の発行が必要となり、景気回復で商品価格が急上昇すると、当局は商品を売却して流動性を吸収する。このような国際商品準備通貨は、世界的な金融管理の潜在的な解決策としても見られてきた(アッシャー、2009年)。バッファーストック当局への資金提供は、当座貸越枠を通じて、または政府や中央銀行が協力してバッファーストックの株式を準備金として保有することによって行われた。意見は分かれたが、世界的な緩衝在庫システムは、グレアム、ハイエク、そしてもともとハート、カルドア、ティンバーゲンが提案したように、最初から商品価格の指数を安定させる総合的なものでなければならないのか、それとも、国際機関が個々の商品価格を安定させるようなシステムの構築において、ケインズ、後にカルドアも志向した、より漸進的なアプローチを追求できるのかということについては意見が分かれた。緩衝在庫支持者間のもう一つの分かれ目は、中央銀行の金融政策をめぐる古い議論に似た、ルールと裁量の問題である。例えば、ハイエク(1948 [1943])は、新自由主義政策ニヒリズムの特徴として、金本位制を模倣するルールを主張した。ケインズ(1974 [1942])は、金融政策だけでなく緩衝在庫の管理においても政策積極主義と裁量に傾倒していた。

新しい国際経済秩序と新自由主義的安定化パラダイムの台頭

1970年代に選択されなかった道としての世界的な緩衝在庫

必須商品の管理の問題は、ブレトンウッズ体制の崩壊と商品価格ショックをきっかけに、国際的議題に戻った(Gilman, 2015; Toye, 2014, pp. 44-47)。農業生産性の伸びの低下と干ばつの相乗効果で、米国と欧州経済共同体の食料商品の余剰在庫は減少した(Shaw, 2007, pp. 115-121)。1972年に世界の複数の地域で同時に作物が不作となったとき、穀物価格は急騰し、OPECの価格決定による原油価格の上昇と商品価格のより一般的な上昇と一致した(Cooper et al., 1975; Garavini, 2019)。価格ショックはグローバル北半球でコストプッシュインフレを引き起こし、飢餓と貧困の一因となった。

南半球の多くの国々で国際収支上の問題が解消され、石油輸出国に大きな収入源がもたらされた(Labys and Maizels、1993年、世界銀行、1982年)。この文脈において、緩衝在庫に関するマクロ経済的主張は新たな重要性を帯びてきた。政治的には、新たに独立した南半球の国々が国連機関で過半数の票を獲得した。石油輸出国機構(OPEC)が一方的に石油価格を引き上げることに成功したことに勇気づけられ、77カ国グループを通じて組織された南半球の国々は経済問題に関してより強力に協調し始めた(Corea、1992年、27ページ、Toye、2014年、43~56ページ)。国内のインフレと商品カルテルの脅威に直面した富裕国政府は交渉に応じる姿勢を示した(Cline、1979年)。南半球諸国は、1974年に国連総会で新国際経済秩序(NIEO)の設立に関する宣言が採択され、最初の勝利を収めた。UNCTADによって導入され、共通基金の創設によって資金が賄われる国際商品計画(IPC)(Cline、1979年、UNCTAD、1977年)は、NIEOアジェンダの基礎となった。南半球諸国が輸入(特に穀物)または輸出に依存している商品、たとえばココア、コーヒー、黄麻、砂糖、鉱物などの2つの必需品グループの緩衝在庫が想定された(UNCTAD、1977年)。1974年にローマで開催された世界食糧会議では、各国が世界食糧安全保障に関する国際約束に合意した。この決議は、各国が保有しながらも国際的に調整された主食の備蓄制度について交渉する意図を宣言した(国連世界食糧会議、1974年)。小麦と米を対象とする国際穀物備蓄制度に関する米国の提案は、1970年代を通じて交渉された (Cline, 1979; Gulick, 1975; Sarris et al., 1979)。結局、NIEO の取り組みは長続きせず、商品価格の安定化に関する議論も例外ではなかった。穀物備蓄に関する交渉は、1970年代末には完了すると見られていたが、最終的にはすべての関係者が受け入れられる安定化の目標価格を特定できなかった (Cline, 1979; Friedmann, 1993)。IPC の共通基金に関する交渉は予想よりもはるかに長引き (基金は 1988 年まで完全に批准されなかった)、この資金調達手段がなかったため、締結された国際商品協定はわずかで、そのいずれも価格安定化を特徴としていなかった (Corea, 1992, pp. 140-145)。 NIEO の創設を促進した政治的、構造的条件があと 10 年続いたならば、おそらく合意に達することができたかもしれない (Corea、1992、pp. 153-162)。

商品価格安定化計画は、輸入国と輸出国、グローバル北半球とグローバル南半球の国々の双方に利益をもたらすケースを強調するよう注意が払われていた。商品市場固有の不安定性と安定化による世界的マクロ経済的利益に焦点を当てた緩衝在庫の古典的なケースが政策構想を支配し、価格安定化策は南北協力と成長というより広範な政策枠組み内で機能すると理解されていた。しかし、在庫の資金調達に誰が貢献すべきか、どの範囲内で価格を安定させるべきか、必要な在庫の規模とその結果のコストに関する交渉は、古典的な枠組みから新古典派の福祉分析へのパラダイムシフトにつながり(Brown、1980、pp. 100-137; Cline、1979; Corea、1992、pp. 136-163)、最終的に新自由主義への道を開いた。新古典派の福祉分析は新自由主義への滑りやすい坂道である。商品価格安定化計画を評価するために新古典派の福祉分析を適用することは、1970年代には目新しいことではなかったが(Kaldor、1980a [1952]、Massell、1969、Oi、1961、Waugh、1944)、1970年代には福祉分析はIPCと共通基金をめぐる交渉において重要な政治的戦場となった。緩衝在庫に関する古典的なケースでは、競争市場における合理的エージェントの行動が、マクロ経済レベルで社会的に次善のダイナミクスにつながる可能性があることが強調されていたが、新古典派の分析では、代表的エージェントを通じて集計を表した(Turnovsky、1978)。これにより、古典的なケースの商品価格の変動による社会的に次善の結果が仮定によって排除された。クモの巣ダイナミクスは、均衡への即時調整を仮定する標準理論に戻ることで完全に置き換えられました (例: Brook and Grilli、1977)。振動と発散のダイナミクス、つまり、セクション 2 で説明されているように、均衡価格の周りまたは均衡価格から離れた市場価格の動き (図 1a、b を参照) は、効率的市場仮説への道を開く合理的期待に関する仮定によって排除されました (Muth、1961、Smith、1978)。市場は均衡に収束するという新古典派の仮定を背景に、不十分な貯蔵と価格変動の問題は、市場の不完全性の 1 つとして再構成されました。不完全な先物市場や保険市場、価格の硬直性、非対称な情報、貿易制限、過剰な投機、政府介入の脅威などが、商品市場が均衡状態に落ち着かない原因と考えられていた(Labys, 1978; Newbery and Stiglitz, 1981; Sarris and Taylor, 1978; Wright and Williams, 1982; Smith, 1978)。緩衝在庫の規模評価の焦点は、民間の貯蔵庫を締め出すことに移った。合理的な市場参加者は公的在庫を考慮するため、緩衝在庫は法外なほど大きくなければならない。

(Hallwood、1977年、HelmbergerとWeaver、1977年、MirandaとHelmberger、1988年、NewberyとStiglitz、1981年、pp. 37-38)。商品価格ショックによってサプライチェーンに沿ったコストプッシュインフレが発生する可能性があるカルドアの2部門世界モデルは、ある商品市場での価格不安定性の発生が他の市場のシフトによって(部分的に)相殺される一般均衡モデルに置き換えられた(Kanbur 1984年、p. 347、NewberyとStiglitz、1981年、p. 19、Smith、1978)。これにより、一般物価水準の変化によるマクロ的な結果は相対価格の変動からほぼ隔離され、インフレはマクロ政策のみの問題となった(Weberら、2024年)。異なる部門別の価格設定体制に関する仮定を放棄したことで、商品輸出国の交易条件が体系的に低下するという理論的可能性も排除された。全体として、ミクロ経済モデルの静的な世界における時間の経過に伴う発展の動的分析が欠如していることは、世界的に双方に利益のあるダイナミクスが考えられなくなったことを意味した。初期の費用便益分析では、消費者と生産者を一緒に考えた場合、より安定した価格が常に福祉を高めることが依然として判明していた (Massell、1969 年、Turnovsky、1978 年)。しかし、新古典派の福祉分析では、安定化による利益は不平等に分配され、長期的には消費者または生産者のどちらかが他方のグループに収入を失うことになる。したがって、一方のグループが他方のグループを補償しない限り、価格安定化は勝者と敗者の物語に変わる。実証研究はすぐに、政策立案者の予想に反して、UNCTAD の IPC に提案された多くの商品について、長期的には南半球諸国が損失を被り、北半球諸国が安定化の純利益を得ることを示唆した (Brook and Grilli, 1977; Labys 1978; Newbery and Stiglitz, 1981, pp. 43-47)。しかし、結果はモデルの仕様に非常に左右され、さまざまな研究の調査結果は決定的ではないことを意味した (Behrman, 1979; Sarris et al., 1979)。長期的には重大な結果をもたらすことになるこの概念的転換にもかかわらず、当時の経済学者の評価は IPC を完全に否定するものでは決してなかった。例えば、クライン(1979、p. 5)がNIEOに対する最も敵対的な意見の1つとして挙げたオルド自由主義者のドンゲス(1977)でさえ、商品価格の安定化にいくらかの利点があるとみていた。当時のミクロ経済学研究者の多くは、自分たちのアプローチの限界について率直に述べていたため、緩衝在庫制度の望ましさについて明確な発言を控えていた(ブラウン、1980年、ニューベリーと

スティグリッツ(1981年)、ブルックとグリリ(1977年)。バッファーストックの廃止がデフォルトの立場になったのは、新自由主義の下でのみである。しかし、新古典派の厚生分析は、非効率的な価格変動という古典的な視点を覆すことで、自由価格と現金補償の優位性という新自由主義の格言への道を開くことになった(イェーガーとザモラ・バルガス、2023年、クレブスとウェーバー、2024年、ウェーバー、2018年)。厚生分析は、成長と発展に利益をもたらすため価格の安定化を目標とするのではなく、不完全性が除去される限り効率的なシグナルと見なされるようになった市場価格の完全な変動を維持しながら、商品価格の不安定性の悪影響に対処することを目的とした代替政策に焦点を移した(ブルックとグリリ、1977年、ニューベリーとスティグリッツ、1981年、pp. 12-16)。この新古典派の立場から、国内レベルで推奨される政策には、より優れた長期の先物市場によって市場の不完全性を排除すること、信用市場や農作物保険へのアクセスを改善する一方で、必要に応じて低所得の消費者や生産者への現金給付に頼ることが含まれていた (Newbery & Stiglitz, 1981, pp. 41-43)。国際レベルでは、情報の改善と貿易の自由化によって競争が改善される一方で、補償金融によって南半球の国々が輸出収入の不足を経験した際に外貨資源が提供される (同書、p. 14、pp. 41-43; Brook and Grilli, 1977)。5価格の安定によって生産者の投資計画能力が向上するなどの目標。インフレ圧力を緩和したり、総需要の安定に貢献したりするという観点は、主な福祉経済分析に加えて考慮すべき緩衝在庫制度の正の外部性へと格下げされたが (Smith, 1978; Sarris et al., 1979; Behrman, 1979)、すぐに削除された。

:14

The failure of the NIEO and the rise of neoliberalism The Volcker Shock in 1979 put an end to the rich country rationale for commodity price stabilization as a tool to fight inflation and restore growth. The Fed’s decision to sharply increase primary interest rates engineered a deep recession in the United States (Panitch and Gindin, 2021, pp. 163-195). Together with fiscal austerity policies this broke the power of labor unions in the Global North (ibid.). Hopes for win-win solutions were replaced with a policy that reasserted dollar hegemony and brought a debt crisis to the global South. With rising interest rates and falling export

5 To be sure, demands for better compensatory measures were also part of the NIEO proposals but were seen as necessary complements to price stabilization, not as alternatives (Corea 1992, p. 16; UNCTAD, 1977).

revenues and exchange rates, a crisis ensued as both public and private actors in the Global South became unable to service their debt (Toye, 2014, pp. 64-66). The contraction of domestic demand in the Global North, limitations imposed on official aid, and a drop in private capital flows created recessions around the world (Corea, 1992, pp. 136-162). During the slow recovery in the Global North countries and a ‘lost decade’ for large parts of Africa and Latin America, commodity prices did not rebound (Corea, 1992, pp. 136-163; Maizels, 1992, pp. 9-20). Matters were made worse when Global South countries scrambled to make up for falling foreign exchange revenues by increasing their production of commodities, thus further depressing prices (ibid.). In the absence of alternative economic mechanisms as envisioned under the NIEO, many Global South countries became dependent on IMF and World Bank loans which subjected them to conditionalities and structural adjustment programs spreading the neoliberal stabilization paradigm internationally under the Washington Consensus (Babb and Kentikelenis, 2018). Global South countries saw their Cereal Boards and domestic price stabilization systems dismantled (e.g. Uganda, Zimbabwe) or considerably weakened (e.g. Kenya) as part of structural adjustment programs (Interviews 12, 13, 14, 20). Repeated devaluations of domestic currencies and a focus on producing more commodities for export to pay back debts and to align production with what was seen as the revealed comparative advantage pushed commodity prices further down (Gilbert 1989). The few commodity agreements that were in place, such as the international cocoa, coffee, rubber, sugar, and tin agreements, helped to cushion the blow of falling commodity prices initially but could not be sustained against persistently depressed prices and without domestic counterparts (Gilbert 1996). In contrast, some of the most successful cases of development in recent decades, the Asian Tigers and China, relied heavily on domestic buffer stocks as part of their development strategy (Dawe, 2001; Dawe and Timmer, 2012; Weber, 2021a). The European Union and the US reduced but never abolished their price support interventions in agriculture (European Commission, 2024; USDA, 2024; Interview 1). But as the logic of the classic case for buffer stocks vanished under neoliberalism, essential commodities have not been considered as an integral part of macroeconomic stability and in the EU and US these stabilization operations occur in the shadows of official economic policies. All that is allegedly needed for economy-wide stability is monetary policy and fiscal discipline, while efficient price signals ensure socially optimal outcomes.

Towards a Post-Neoliberal Stabilization Paradigm: The Case of Food Staples Food staples are the most essential of the essentials. Most people depend on maize, wheat, and rice to achieve minimum levels of dietary energy requirements (IMF, 2023). Price increases in these staples can destabilize whole societies and economies (Fischer, 1999, Interviews 12, 13). This has become once more salient in the world food crisis 2020-2023. We have hence picked this sector to illustrate the case for a post-neoliberal stabilization paradigm following the classic buffer stock reasoning. In the food sector, the neoliberal playbook has been implemented since the 1980s. This is reflected in recommendations for agricultural trade liberalization and a scaling back of market interventions (OECD, 2023; World Bank, 2012, pp.117-136); a reliance on lump-sum payments (Díaz-Bonilla, 2021; Galtier and Vindel, 2013, pp. 35-37); and an expansion of future markets and crop insurances (ibid.; Beaujeu, 2016; FAO et al., 2011) to handle price volatility. But this approach relies on the assumption of efficient price signals and a separation of relative price changes and macro-outcomes. We show that both are not warranted. Food price spikes are not efficient After low and stable food prices in the 1980s and 1990s, food prices and volatility have increased since the beginning of the century (Ahmed et al., 2014; Figure 2a). This culminated in the 2007-2008, 2010-2012 and the 2020-2023 food price crises (see Figure 2). Most food experts acknowledge a general tendency of food prices to be volatile (Kalkuhl et al., 2016; Kharas, 2011). Small changes in quantities lead to large price swings due to low supply and demand elasticities while natural shocks such as weather and pests frequently affect agricultural output (FAO et al., 2011). Yet, the origins of food price volatility continue to be interpreted from competing theoretical vantage points (Gouel, 2012). There are two basic models: endogenous instability in a cobweb dynamic driven by lagged adjustments and forecasting errors which justifies government intervention (classic case); and rational expectations where instability results from exogenous shocks and government intervention disturbs price signals (neoliberal) (ibid.). The rational expectations model holds that “in recurrent situations the way the future unfolds from the past tends to be stable, and people adjust their forecasts to conform to this stable pattern” (Sargent, 2022). We argue that if patterns ever were stable, situations are certainly not recurrent and there are no such stable patterns in times of overlapping emergencies. We are in Keynes’ world of fundamental uncertainty, herd behavior, and

animal spirits. In this world, price explosions are not efficient signals that result in socially optimal outcomes. Empirically, it is challenging to pin down the precise combination of drivers of the recent food crisis when prices reached historic highs (see Figure 2). Several national and international short-run factors overlapped and structural features of the system helped fuel the price explosion (Algieri et al., 2023). In 2020-2022, global production and stock levels were in principle adequate in contrast to the 2008 crisis, but food prices spiked in response to the uncertainty (Ghosh, 2023; IPES-Food, 2022; van Huellen and Ferrando, 2023). Food prices were on the rise in 2021 following pandemic-related supply chain disruptions. In 2022, in response to anticipated supply shortages resulting from the Russian invasion of Ukraine, one of the world’s most important producer of grain and seed oils, prices jumped (Kornher and von Braun, 2023). While the Russia-Ukraine war led to temporary local threats of physical shortage in countries that primarily rely on grain imports from these regions, the global supply of grain, was still more than high enough to cover global demand in the medium-run (IPES-Food 2022, p. 10). What ultimately threatened people’s access to grain was not necessarily the pace of adjusting shipping routes to import grain from new destinations but also the spike in grain and shipping prices on the international market that resulted from uncertainty about supply conditions and speculation (ibid.). It used to be considered a rule of thumb that the price goes up when storage in key countries goes down. But this has been questioned since the financialization of the 2000s. Even believers in the rule, like a trader we interviewed, concede that in 2022 “prices were decoupled from the market mechanism as we know it in our business [referring to this rule of thumb] and were driven by the uncertainty of Ukrainian and Russian exports” (Interview 10). There was a similar discussion about how uncertainty about supply conditions exacerbated food price spikes in the 2008 food crisis (FAO et al., 2011). Several input costs for grain also shot up in 2022, triggered by the same uncertainties. Food and oil prices are highly correlated and fossil fuels are an important input for the food sector (IMF 2023, Interview 3). Nitrogen fertilizers require gas and the sanctioned allies Belarus and Russia are important exporters in a globally highly concentrated market (Algieri et al., 2023; van Huellen and Ferrando, 2023). Among other factors like medium term impacts of supply chain disruptions during the Covid pandemic, the gas price spikes resulted in fertilizer prices shooting up by almost 200

percent year-over-year in April 2022 (YCharts, 2024). Several indices of ocean freight rates also multiplied (FAO, 2021a; FAO, 2022). It is likely that the grain price spike was exacerbated by procyclical speculation. To be sure not all financial transactions on grain markets are speculative. Future markets were born in agriculture as a way for producers to hedge against uncertain prices at the time of harvest (Morgan, 1980; UNCTAD, 2023a, pp. 72-99). Millers also rely on future markets to hedge price uncertainty (Interview 6). Yet, farmers with storage capacity and firms along the supply chain can engage in commercial speculation by increasing holdings of raw materials in anticipation of higher prices. This can involve herd behavior (Interview 3). One result is the so-called bullwhip effect that amplifies shortages and price increases in situations of input supply uncertainty (Rees and Rungcharoenkitkul, 2021, Interview 6). In addition, export controls and panic-buying by overreacting governments can drive-up prices (IMF, 2023; Pinstrup-Andersen, 2014). Pure financial speculators benefit from grain and fuel price volatility in commodity markets. The flipside of the dismantling of government price stabilization in the neoliberal era has been a rapid expansion of derivative markets and an influx of banks, private equity, and hedge funds (Staritz et al., 2018; Tröster, 2018; Ederer et al., 2016). During both recent food price crises investments of financial speculators increased, betting on rising future prices (Algieri et al., 2023; Kornher et al., 2022; UNCTAD, 2023a, pp. 76-84; Interview 3). Financial investments fell with prices in the second half of 2022 (ibid.). One mechanism for how financial speculators amplify price fluctuations is “trend-following”, which involves high frequency trading with “algorithms that spot rising or falling prices and automatically buy or sell derivatives in response” (Gibbs and Ross, 2023). Commercial and financial speculation also merge in grain markets. Five companies, the so-called ABCCDs - ADM, Bunge, COFCO, Cargill, and Louis Dreyfuss, control 70 to 90 percent of the global grain trade (IPES-Food, 2022; Hietland, 2024). They reaped record profits in 2022 (UNCTAD, 2023a) and are known to benefit from crises and volatility (Salerno, 2017). These gigantic conglomerates with hundreds of subsidiaries spanning the whole supply chain include sizable financial arms not regulated as banks (ibid.). They have built up inhouse intelligence on global agriculture that exceeds that of states (Morgan, 1980, Interviews 17, 19, 21). The combined storage capacity of the giant grain traders is unknown but must be enormous, dwarfing that of most countries and incomparably larger than those of other participants in the supply chain. Just three

companies (ADM, Bunge, and COFCO) can store as much wheat as the total annual consumption of the US, UK, and Turkey combined (Hietland, 2024). The International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems (IPES-Food) warns that the agricultural grain traders have incentives to “hold stocks back until prices are perceived to have peaked” (IPES Food, 2022, p. 14). Especially given that small changes in supply can trigger large price swings, the ABCD may well have a hand in exacerbating price volatilities (Hietland, 2024), even though a lack of data about storage levels and financial positions makes it difficult to prove (UNCTAD, 2023a). In contrast to farmers, financial speculators including grain traders also gain when prices fall. Since they bet on both upward and downward movements, they benefit from amplified price volatility (UNCTAD 2023). Commodity traders and hedge funds have now put the largest bet in 20 years on a slump in grain prices (Savage and Steer, 2024). Planted acreage is coming down in many countries as farmers respond to plummeting prices. Market observers see the beginning of a new price cycle (ibid.). It resembles the over- and undershooting of prices in the cobweb model. It is contested since the 1970s debate to what extent speculation drives price volatility (Smith, 1978). The debate also flared up in the 2007-8 crisis (Torero, 2016). It is hard to see how in situations of enormous uncertainty speculative storing and bets would not amplify price swings, even if the precise magnitude of price movements due to inflation is difficult to pin down empirically. As a result of trade liberalization, domestic prices are coupled with international prices (Ahmed et al., 2014). In Germany, for example, there was at no time any threat of a domestic shortage in 2022-2023, but since domestic grain prices follow the Paris grain exchange, they shot up (Interviews 4, 5, 6, 9, 10). For Sub-Sahara Africa the passthrough from global to domestic food staple prices is estimated to be 100 percent (Okou et al., 2022). But even when international prices are stable, poor countries often experience price spikes due to domestic supply disruptions (ibid., Ahmed et al., 2014; Baltzer, 2014; Interviews 12, 14). The consequences of the food price shock and the crisis of neoliberal stabilization Fifteen years of progress in reducing global undernourishment has been reversed as a result of the world food price crisis (IMF, 2023). Global hunger has jumped up from affecting 7.9 percent of the world population in 2019 to 9.2 percent in 2022 (FAO et al., 2023). Even in rich countries like the

U.S., food insecurity increased sharply from 10.5 percent of the population in 2019 to 12.8 percent in 2022 (Rabbitt et al., 2023). Food banks in rich countries are overwhelmed (Feeding America, 2022; Tagesschau, 2023; The Greater Boston Foodbank, 2023, Interview 22). At the same time, the macroeconomic consequences of the food price shock are what we would expect from the perspective of the classic case for buffer stocks. Global food price increases translate into rising domestic food inflation as high levels of concentration along the value chain enable a pass through of costs. The IMF (2023, p.5) estimates that the passthrough rate is 0.3 percent with higher rates for Global South countries and economies with greater trade openness. Food price inflation has been high in poor and rich countries, outpacing overall inflation (see Figures 3a, 3b; Rother et al., 2023). Rising food prices have increased headline inflation (see Figure 4). In Global South countries like Egypt, Uganda, Kenya, Nigeria, and Pakistan, food price increases accounted for more than half of the overall price increase in 2023 (see Figure 5). Even in a rich country like Germany, food price increases accounted for almost a quarter of year-on-year inflation in January 2023 (ibid.). The two-sector reasoning of the classic case for buffer stocks can help in understanding the transmission from commodities to final food prices. While food commodity prices are volatile, processed food shows smoother price movements (see Figure 6 for the example of the US food sector). We can trace this pattern in the supply chain from grain via flour to bread drawing on the German example (see Figure 7). In interviews with millers, we learned they set their profit margins as a monetary markup over a given quantity of outputs (Interviews 5, 6). In stable times, mills compete by squeezing operating costs. But in times of major shocks and uncertainty, they switch to increasing markups to protect themselves against input price increases. In the words of a miller: “competition becomes much less intense in times of shocks as everyone sets prices to save their business not to gain market shares.” As a result, increased grain and energy prices are not just passed on fully but markups also increase (Interview 6). Large firms tend to be in a stronger position than smaller ones to take advantage of shocks, so that emergencies can further increase concentration. When input markets calm down and competition returns, markups fall again, and prices go down. Accordingly, wholesale flour prices went up with bread wheat prices and fell with them (Figure 7) – albeit at a somewhat slower pace displaying the well-known ‘up like rockets, down like feathers’ pattern (Bacon, 1991).

At the bakery stage, raw material costs become less important, and wages and energy costs have a higher weight (Destatis, 2024; Interviews 2, 8, 11). Output is no longer as homogenous as flour and there is scope for product distinction. Margins are set in relation to total costs, not weight (Interview 7). This implies that if costs go up, unit profits go up even if relative margins are stable (Hahn, 2023). But as the price shock can also lead to a reduction in price competition, margins might also rise (Interview 7). Widely broadcasted cost increases as in the case of the grain crisis present opportune moments for price increases (Weber and Wasner, 2023, Interview 1). Prices of bread, bread rolls, and other baked goods went up with wheat prices but did not fall when energy and raw material prices declined in 2023 (Figure 7). This has likely generated some windfall profits, especially for larger bakeries. What we can see in the German bread sector are indications of sellers’ inflation in the sense that the pricing decisions of firms with market power to protect margins translate the price shocks in inputs into generalized inflation (Weber and Wasner, 2023). The mechanism is the ratchet effect described by Kaldor (see section 2). First studies on profits and prices for the food sector more broadly also point to sellers’ inflation (Jobst and Duthoit, 2023; Pancotti et al., 2024; van Huellen and Ferrando, 2023). Allianz Research (Jobst and Duthoit, 2023) suggests that 10 percent of European food price inflation cannot be explained by their model and attributes this to profit-taking pricing, whereas packaged food companies have increased prices more than retailers. Oliver Wyman (2023) finds that across Europe food retailers have protected their margins despite rising costs, which has driven up profits. Food price inflation reduces real incomes of households and exacerbates inequalities. The income share spent on food varies widely between poor and rich countries ranging from close to 60 percent in countries like Kenya, Burma, and Nigeria to less than 10 percent in Switzerland and the United States (USDA, 2023). Poorer households in rich countries also spend larger shares of their income on food. In the U.S., for example, the lowest quintile spent 31.2 percent and the highest a mere 8 percent of their income on food in 2022 (USDA, 2024b). At the height of inflation in Germany in October 2022, there was a wedge of 3.4% between the inflation rate experienced by low-income households with two kids (11.8%) and the inflation experienced by a high-income single household (8.4%) (Endres and Tober, 2022). The erosion of purchasing power due to higher food prices can exert downward pressure on growth.

The incomes of whole nations are affected by the food price spike (Moseley et al., 2015). 70 percent of global wheat exports are produced in five countries and four countries produce 85 percent of global corn exports (Wiggerthale, 2022). Meanwhile most countries rely on grain imports while also being import dependent on farm inputs (Varghese and Suppan, 2023). Between 2021-2022, Low Income Countries experienced an increase in their import bill for farm inputs of 65% (FAO, 2022). And between 2020 and 2021 Global South countries saw their food import bill rise by 20%, where two thirds of the increase was due to higher prices (FAO, 2021a). In the two subsequent years import volumes fell by 10%, indicating that Global South countries paid even higher prices to get less food (FAO, 2022, 2023). This is extremely worrying from a food security perspective as it indicates that these countries had to reduce their import of food staples because they were unable to finance the necessary purchases on international markets. Many Global South countries are specialized in agricultural exports and logged in at the bottom of the global diversification hierarchy dating to colonial times (Interviews 12, 14, 17; UNCTAD, 2023b; Weber et al., 2022). When prices for both imported and exported commodities spike at the same time, increased export revenues may not compensate for alleviated import costs as Kaldor already warned. The earnings of a price spike on commodity exports can translate into temporarily higher profits that might not be re-invested domestically nor taxed but leave the country (Ndikumana and Boyce, 2022). Increases in agricultural export commodity prices can also divert land from food production, exacerbating import needs (Interview 21). Food crop prices are essential for the incomes of hundreds of millions of farmers. In many Global South countries, farming is the main income source for large parts of the population, so that such price swings have major macroeconomic repercussions (Interviews 12, 14, 15, 16; Lowder et al., 2019). But farmers in Europe, too, feel squeezed as agricultural commodity prices have been falling faster than fertilizer prices (Cokelaere and Brzezinski, 2024). This was among the grievances fueling the farmers’ protests we saw across Europe in 2024. The import price shocks occurred against the background of a decade of rising debt levels in many Global South countries and enormous fiscal pressures during the COVID-19 pandemic. It triggered a debt crisis (IPES-Food, 2023). The strengthening of the US dollar as safe haven currency in a moment of global turmoil and the weakening of domestic currencies as a result of increased import needs increased the debt burden (IMF, 2023; Interviews 12, 13, 14).

The debt crisis has been made worse by the neoliberal stabilization response. Rapid interest rate increases by the Fed and ECB pushed some Global South countries into sovereign default such as for example Ghana, Sri Lanka, Suriname, Zambia (IPES-Food, 2023; UNCTAD, 2023a, p.63). In an attempt to fend off capital outflows interest rates in many Global South countries were hiked even more aggressively than in the US or Europe (Adrian et al., 2024). Many Global South countries are caught up in a vicious cycle of food insecurity, price volatility, debt, and austerity (Mohammed et al., 2023; UNCTAD, 2023a, p.73). Despite having documented the devastating macroeconomic and development consequences of food price shocks in detail, the IMF (2023, p. 17) still recommends the standard neoliberal policy package: monetary and fiscal tightening; fiscal support measures where necessary to support vulnerable groups “should preserve the price signal” and “reducing taxes on food and fuel is not advisable”. An interview partner in Kenya (Interview 13), for example, shared that the public buffer stock system and tax breaks helped to stabilize food and fertilizer prices. But IMF structural adjustment measures in response to the looming debt crisis will undermine this stabilization efforts. Procyclical interest rate hikes, austerity, and price volatilities in essentials damage long-term investments in Global South countries that would be needed for structural change, resilience, and climate adaptation (Mohammed et al., 2023; UNCTAD, 2023a; Interview 14). In contrast, to stabilize their domestic economies rich countries eventually diverged from a pure neoliberal playbook. The U.S. used its position on top of the monetary hierarchy to pursue aggressive fiscal policies despite inflation. It mobilized the Strategic Petroleum Reserve against the energy price shock and the USDA helped stabilize the farm sector with direct purchase programs during the pandemic (USDA, 2022; USDOT, 2022). European countries against the best advice of neoliberal economists implemented a range of energy price controls. The IMF estimates that such “unconventional fiscal policies” contributed significantly both to reduce inflation and stabilize output (Dao et al., 2023). More than a third of advanced economies among the G20 announced energy and/or food price controls and subsidies (IMF, 2023). France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Portugal, Romania, Slovenia, and Spain introduced various forms of price stabilization for energy (Amaglobeli et al., 2023; Krebs and Weber, 2024). Japan, Austria, Slovenia, Albania, Croatia provided subsidies to farmers to compensate them for higher input prices (e.g. fertilizers, diesel) (ibid.). European countries also used public intervention purchases to stabilize agricultural markets during the pandemic (Interview 1). Nevertheless, the world economy has seen growth slow as a result of the monetary tightening in response to inflation (World Bank, 2024).

:23

NIEOの失敗と新自由主義の台頭

1979年のボルカーショックは、インフレと闘い成長を回復するための手段としての商品価格の安定化という富裕国の論理に終止符を打った。FRBがプライマリー金利を大幅に引き上げる決定を下したことで、米国は深刻な不況に陥った(パニッチとギンディン、2021、pp. 163-195)。財政緊縮政策と相まって、これはグローバル北半球の労働組合の力を弱めた(同上)。ウィンウィンの解決策への期待は、ドルの覇権を再確認し、グローバル南半球に債務危機をもたらした政策に取って代わられた。金利の上昇と輸出の減少により、

5 確かに、より良い補償措置を求める声もNIEO提案の一部であったが、それは価格安定化の代替策ではなく、価格安定化に必要な補完策として捉えられていた(Corea 1992、16ページ;UNCTAD、1977年)。

外貨収入と為替レートの急激な低下により、南半球の公的および民間セクターの両方が債務返済不能となり、危機が生じた(Toye, 2014, pp. 64-66)。北半球の国内需要の収縮、公的援助の制限、民間資本フローの減少により、世界中で不況が生じた(Corea, 1992, pp. 136-162)。北半球諸国の回復が緩慢で、アフリカとラテンアメリカの大部分が「失われた10年」を過ごした間、商品価格は回復しなかった(Corea, 1992, pp. 136-163; Maizels, 1992, pp. 9-20)。南半球諸国が外貨収入の減少を商品の生産増加で埋め合わせようと躍起になり、価格がさらに下落したことで、事態はさらに悪化した(同上)。 NIEOで想定されたような代替経済メカニズムが存在しなかったため、多くの南半球諸国はIMFや世界銀行の融資に依存するようになり、ワシントン・コンセンサスの下で新自由主義安定化パラダイムを国際的に広める条件や構造調整プログラムの対象となった(Babb and Kentikelenis、2018)。南半球諸国では、構造調整プログラムの一環として、穀物委員会や国内価格安定化システムが解体された(ウガンダ、ジンバブエなど)か、大幅に弱体化した(ケニアなど)(インタビュー12、13、14、20)。度重なる国内通貨の切り下げと、債務返済と明らかにされた比較優位と見なされるものと生産を一致させるために輸出向け商品の生産を増やすことに重点が置かれたことで、商品価格はさらに下落した(Gilbert 1989)。国際ココア、コーヒー、ゴム、砂糖、スズ協定など、当時存在していた少数の商品協定は、当初は商品価格の下落による打撃を和らげるのに役立ったが、長期にわたる価格低迷に対しては、国内の同等協定なしには維持できなかった (Gilbert 1996)。対照的に、ここ数十年の開発で最も成功した事例のいくつかであるアジアの虎と中国は、開発戦略の一環として国内の緩衝在庫に大きく依存していた (Dawe、2001; Dawe and Timmer、2012; Weber、2021a)。欧州連合と米国は、農業における価格支持介入を削減したものの、廃止することはなかった (欧州委員会、2024; USDA、2024; インタビュー 1)。しかし、バッファー在庫の古典的な根拠の論理は新自由主義の下で消え去り、必需品はマクロ経済の安定に不可欠な部分とはみなされなくなり、EUと米国ではこれらの安定化策は公式の経済政策の影で行われている。経済全体の安定に必要なのは金融政策と財政規律だけであり、効率的な価格シグナルが社会的に最適な結果を保証するとされている。

ポスト新自由主義安定化パラダイムに向けて:主食のケース 主食は、生活必需品の中でも最も重要なものである。ほとんどの人は、最低限の食事エネルギー要件を満たすために、トウモロコシ、小麦、米に依存している(IMF、2023年)。これらの主食の価格上昇は、社会や経済全体を不安定化させる可能性がある(Fischer、1999年、インタビュー12、13)。これは、2020~2023年の世界食糧危機において再び顕著になっている。そのため、私たちはこの分野を取り上げ、古典的な緩衝在庫の理論に従ったポスト新自由主義安定化パラダイムの事例を説明することにした。食品分野では、1980年代から新自由主義の戦略が実施されてきた。これは、農業貿易の自由化と市場介入の縮小に関する勧告に反映されている(OECD、2023年、世界銀行、2012年、pp.117-136)。価格変動に対処するために、一括払いへの依存(Díaz-Bonilla、2021年、GaltierおよびVindel、2013、pp. 35-37)、先物市場および作物保険の拡大(同上、Beaujeu、2016年、FAO他、2011年)が挙げられます。しかし、このアプローチは、効率的な価格シグナルと、相対的な価格変動とマクロの結果の分離という仮定に依存しています。私たちは、その両方が正当化されないことを示しています。食料価格の急騰は効率的ではありません。1980年代と1990年代の食料価格の低位安定の後、今世紀初頭以降、食料価格と変動性が上昇しています(Ahmed他、2014年、図2a)。これは、2007~2008年、2010~2012年、および2020~2023年の食料価格危機で頂点に達しました(図2を参照)。

食品専門家の多くは、食品価格が一般的に変動しやすい傾向にあることを認めている (Kalkuhl et al., 2016; Kharas, 2011)。供給と需要の弾力性が低いため、数量の小さな変化でも価格が大きく変動する一方、天候や害虫などの自然災害は農業生産に頻繁に影響する (FAO et al., 2011)。しかし、食品価格の変動の原因は、競合する理論的観点から解釈され続けている (Gouel, 2012)。基本的なモデルは 2 つある。1 つは、遅れた調整と予測誤差によって引き起こされるクモの巣のようなダイナミクスにおける内生的不安定性で、政府の介入が正当化される (古典的なケース)。もう 1 つは、外生的ショックによって不安定性がもたらされ、政府の介入が価格シグナルを乱す (新自由主義的) 合理的期待モデルである (同上)。合理的期待モデルは、「繰り返される状況では、過去から未来が展開する方法は安定する傾向があり、人々はこの安定したパターンに合わせて予測を調整する」としている (Sargent, 2022)。パターンが安定しているとしても、状況は確実に繰り返されるものではなく、緊急事態が重なり合う時期にはそのような安定したパターンは存在しないと我々は主張する。我々はケインズの根本的な不確実性、群集行動、そして

アニマルスピリット。この世界では、価格爆発は社会的に最適な結果をもたらす効率的なシグナルではありません。経験的に、価格が史上最高に達した最近の食糧危機の要因の正確な組み合わせを特定することは困難です(図2を参照)。いくつかの国内および国際的な短期的要因が重なり合い、システムの構造的特徴が価格爆発を助長しました(Algieri et al.、2023)。2020~2022年には、2008年の危機とは対照的に、世界の生産と在庫レベルは原則として適切でしたが、不確実性に応じて食品価格が急騰しました(Ghosh、2023; IPES-Food、2022; van HuellenとFerrando、2023)。パンデミックに関連したサプライチェーンの混乱を受けて、2021年には食品価格が上昇しました。 2022年、穀物と種子油の世界有数の生産国であるウクライナへのロシアの侵攻により、供給不足が予想される中、価格が急騰した(Kornher and von Braun, 2023)。ロシア・ウクライナ戦争により、これらの地域からの穀物輸入に主に依存している国々では一時的に物理的な不足の脅威が生じたが、世界の穀物供給量は中期的には世界の需要を満たすのに十分以上であった(IPES-Food 2022, p. 10)。人々の穀物へのアクセスを最終的に脅かしたのは、必ずしも新たな目的地から穀物を輸入するために航路を調整するペースではなく、供給状況の不確実性と投機から生じた国際市場での穀物価格と輸送価格の急騰でもあった(同上)。かつては、主要国の貯蔵量が減少すると価格が上昇するという経験則と考えられていた。しかし、これは2000年代の金融化以降疑問視されてきた。私たちがインタビューしたトレーダーのように、このルールを信じている人でさえ、2022年には「価格は、私たちの業界で知られている市場メカニズムから切り離され(この経験則を参照)、ウクライナとロシアの輸出の不確実性によって左右された」と認めています(インタビュー10)。 2008年の食糧危機では、供給状況に関する不確実性が食料価格の急騰を悪化させたという同様の議論がありました(FAO他、2011年)。 穀物のいくつかの投入コストも同じ不確実性によって引き起こされ、2022年に急騰しました。 食料価格と石油価格は高度に相関しており、化石燃料は食料部門にとって重要な投入物です(IMF 2023、インタビュー3)。 窒素肥料にはガスが必要であり、制裁対象の同盟国であるベラルーシとロシアは、世界的に高度に集中した市場で重要な輸出国です(Algieri他、2023年、van HuellenとFerrando、2023年)。新型コロナウイルスのパンデミックによるサプライチェーンの混乱による中期的な影響など、他の要因の中でも、ガソリン価格の高騰により肥料価格が200%近くも上昇した。